A tiny microcatheter can be guided deep into the brain

Researchers have developed a magnetic catheter capable of navigating deep within the brain without damaging blood vessel walls.

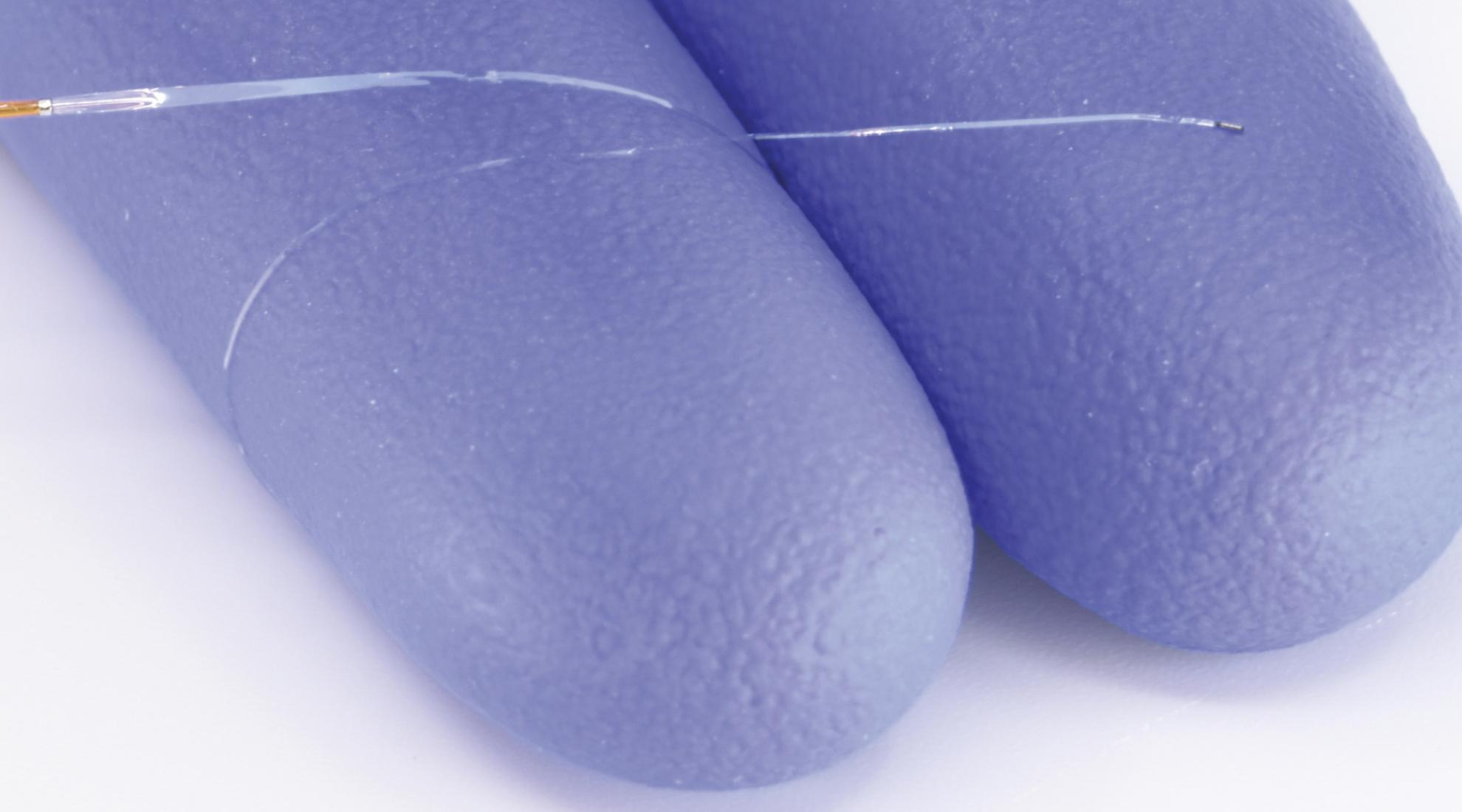

The catheter, named MagFlow, was developed at EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland and is remarkable in two respects: it is only half the size of conventional microcatheters and it moves in an entirely new way. Rather than being actively pushed forward, it is carried by the bloodstream, with its tip precisely controlled by an external magnetic field. The results of the experiments were recently published in Science Robotics.

Joystick-based control

The microcatheter comprises a tiny tube filled with a therapeutic agent and a magnet at its tip. A medical practitioner uses a joystick to control a magnetic-field generator, which in turn orients the magnet and, consequently, the catheter’s tip. The key innovation is that the bloodstream itself supplies the forward motion. This means that the catheter goes with the flow, reducing contact with the vessel walls and thereby lowering the risk of damage.

The joystick used for directional control is called OmniMag and was developed at the Micro Biorobotic Systems Laboratory. OmniMag automatically calculates the magnetic field orientation required to guide the magnetic tip of the MagFlow catheter in the desired direction. The clinician operates the joystick using a robotic arm.

Successful trials in pigs

In experiments conducted at a research facility in Paris, the team demonstrated MagFlow's unique capabilities by steering the tiny, untethered microrobot through the narrow, curved arteries of pigs' heads, necks and spines to deliver contrast and embolising agents. Due to its ultraminiaturised design, the catheter can access vessels as narrow as 150 microns in diameter— about the width of a human hair. Conventional microcatheters could not reach these distal, tortuous vascular branches without posing a significant risk.

Potential use in treating eye tumours

The research group is currently working with medical specialists from Lausanne University Hospital and the Jules Gonin Eye Hospital to make the technique available to patients with retinoblastoma, a type of cancer that affects the retina. In the longer term, they also plan to use the technique for neurological applications, such as mapping brain activity during epileptic seizures. To this end, the team is collaborating with neurosurgeons and epileptologists at the Inselspital Bern.